The Feminist History of Collage (Part 1)

“Girls Will Be Girls”

Most recognize the art of mixed media collage as an invention by artists such as Pablo Picasso, Juan Gris, or Georges Braques in the collage phase of the Cubist movement from 1912-1914, when they popularized the medium and thrust it onto the the international art scene and gave it the legitimacy needed to be defined as valid artform. Although the technique of cutting and pasting paper together is as old as the invention of paper itself in 5th century China; the beginning of collage as we recognize it today comes from much more unassuming place: inside the homes of aristocratic women during the long 19th century.

In 1771, a century and a half before Picasso, Gris, or Braques were born, 71 year old English widow, Mary Delany, would begin the first of her “paper mosaiks,” in which she would take a multitude of different media such as hand dyed paper, tissue, and occasionally, watercolor paints to create life sized, botanically accurate depictions of plants. After the death of her second husband in 1768, Mary would join the Blue Stocking movement, (a proto-feminist group that championed the education of women,) was able to benefit from the freedoms that came with being a widow, and started fully pursuing her own interests and acquaintances. One of her closest friends and future patroness, Margaret Bentinck, Dowager Duchess of Portland, would encourage and share her love of botany and together, the two women would familiarize and develop a deep knowledge of the subject. As her love for the topic expanded, Mary sought new and interesting ways to demonstrate her knowledge and artistic hobbies and combined her two passions to create her floral paper cutting techniques.

Inspired by the fashionable passtime amongst ladies of the time, découpage, or the hand cutting and pasting of decorative motifs onto cabinets, trinket boxes, and other furniture, she instead would use these papers to cut apart and create her ‘mosaiks.’ In order to depict these specimens as lifelike, she would cut and stack hundreds of colored papers and tissues ontop of eachother several layers thick, to accurately capture the structure, tones, shading, and texture of the flower she was illustrating. Her paper mosaiks were so realistic that many contemporaries believed her works to be painted watercolors, and she quickly gained recognition for her skills. Many patrons, including King Georges III & Queen Charlotte, would befriend, commission, and financially support her; through these associations in court and her reputation as an artist, women of letters, and amateur botanist, she was in contact and exchanged ideas with many of the great thinkers of her time such as Jonathan Swift, Constantia Grierson, and George Ehret. By the end of her art career in 1782, when her failing eyesight forced her to retire her scissors and glue, she had spent the last 11 years creating a total of 985 of these collages, and would live off a generous pension and home in Windsor, given to her by the king, where she died in 1788.

The next wave of collage would come during the ‘cartomania’ craze of 1860’s England as the popularity of having your portrait photographed, printed as a carte de visite, (an early form of a business card) and exchanged amongst friends and larger society became a fashionable form of what we might recognize today as social media. In order to organize and display who was -or wasn’t- included in certain families and social circles, these vast collections of cartes de visites were meticulously and intentionally arranged in photo albums to denote people’s importance, reach, and influence in these circles. These decorated photo albums would then be shown, discussed and added to by friends and family members as a way to convey a lady’s talent much in the way embroidery was. As aristocratic women would have the time and money to collect and exchange numerous cartes de visites and arrange them in albums, some of them would experiment with these photographs and search for an artistic way to depict their lives and relationships with the individuals pictured; as well as express their creativity, wit, and humor amongst their peers.

One such example of a collage that subtly and humorously comments on a lady’s social circle and depicts a typical domestic scene is in Lady Filmer’s Lady Filmer in Her Drawing Room. In it, Lady Filmer had used watercolors to paint the background of her salon and placed her closest relations around her either as physical guests in her home or as portraits that hang in the painted frames above her. The Art Institute of Chicago, which houses the work, explains the politics of the collage and the placement of some of her subjects as:

“Here she placed herself at the heart of a gathering of fashionably attired friends and family, making a photocollage album—that is, performing the very activity that produced this work. The composition revolves around Filmer’s most important guest: Albert Edward, the Prince of Wales, with whom she certainly flirted and may even have had an affair. The prince is shown leaning against the table, his hat at a rakish angle and waistline trimmed flatteringly by Lady Filmer’s knife. By contrast, her husband, Sir Edmund Filmer, is shown in the lower right—near the family dog.”

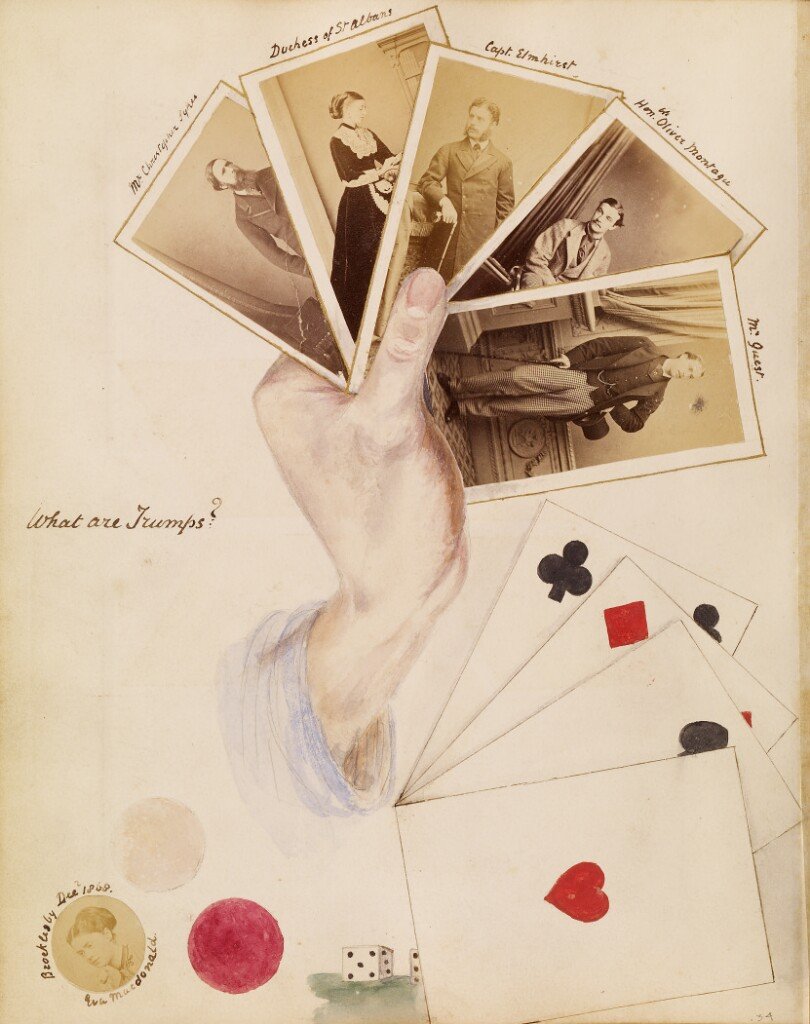

Lady Filmer’s collage places her and her perspective at the literal and metaphorical center of the work; she references her personal passion of creating and her alleged flirtation with the Prince of Wales, going so far as to face her own portrait towards his with her back turned to her husband’s portrait. She doesn’t attempt to censor or hide the truth of her current affairs in her life, rather it seems she took a certain pride and pleasure from her situation and ensured that it was portrayed and preserved in her own perspective. Not every collage that was made by the Victorians was as literal in its depiction of these relationships; there are also examples of more whimsical and imaginative works, such as Eva Macdonalds “What Are Trumps?” In this piece, similarly to Lady Filmer, Eva used both watercolors and cartes de visites, but instead of a literal domestic scene, she contextualizes these relationships with the analogy of cards, dice, and gambling chips; one of which she has put her own photo onto and signed. This version of visual storytelling allows her to draw parallels between the intrigue and gambling that was present in with her relationships to that of a winning hand (called a ‘trump‘ in a game of cards) signifying their positive attributes in the navigating of her life and social affairs.

These works allowed them to freely represent their ‘politics’ amongst some of their peers, as well as serves as a way for Lady Filmer, Eva Macdonald and other women who collaged, to use their own autonomy to craft, communicate, and preserve themselves and their lives stories without being impeded in the way that women would have been should they have pursued a more ‘traditional’ or ‘noble’ form of art reserved for men. In an era in which we look back upon and remember the stuffiness and misogyny of the time, there is something comforting and inspiring about seeing women use the means available to them to take part in creating art and take part in their own versions of these creative spheres and history they were so often otherwise denied access to.

As the 19th century came to a close and the world began its plunge into modernity, two important factors would radically change the landscape for female collage artists over the next 70 years; the first would come in the form of mass produced photojournalism, which allowed for women of all economic backgrounds access to many forms of photography, advertisement, and typeface to work with for their pieces, the second is the birth of the Women’s Suffrage movement, which was one of the first large scale groups to advocate for the enfranchisement of women. While the suffragette movement would end at the start of World War I, the combination of these movements and the unprecedented need for women to take over traditional men’s work as the war raged on would give birth to unseen levels of social, economic, and personal independence for women, and the “New Woman” ideal that would define First-wave feminism in the interwar years.

While most suffragette movements began in the later half of the 19th century before the first world war, the “New Woman” ideal took off during the interwar years where various countries were experiencing major political shifts, mass industrialization and gender/population imbalance due to the sheer number of dead men from the war. This movement was particularly popular in Germany, where not only were they experiencing the same upheaval and cultural shifts as other countries, but also the effects of the Treaty of Versailles which bred political chaos in the later half of the 1920’s into the 30’s and 40’s.

Times of political upheaval often give birth to new political, technological, and artistic movements, so it’s only natural that the turbulent interwar years of Germany’s Weimar Republic gave birth to the Dadaist movement which was founded on the ideals of anticonformity, irrationality, and a call to burn down the traditional, rigid social norms that had defined life in prewar Europe. Hannah Höch, the only female collage artist of the Dada movement that would gain similar recognition for her work as her male peers, would not only become one of the defining collage artists of interwar Germany, she would identify with, embody and infuse the ideals of the “New Woman” in her lifestyle and her art. This mix of perspectives allows her collages to be a unique criticism of contemporary society in her intersection of anti-capitalistic dadaist principals and first wave feminism.

In her 1919 collage, Cut with a Kitchen Knife Dad Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany, the chaos of the era seems to jump off the page; we see at its center, a female dancer juggling her head in her hands while she pirouettes in the midst of machinery, Weimar politicians, her dadaist peers and various sized typefaces with messages such as: “Das neue Frauenbild/The new image of women”, “Dadaisten gegen Weimarer Bierbauchkultur/Dadaists against the Weimar beer-belly culture,” and “Es leben die unabhängigen Männer/ Long live the independent men." The woman is also used as a divider between the anti-dadist, patriarchal symbols of the top half of the collage and the pro-dadist, feminist bottom half. Höch’s choice to place the ballerina between the two opposing worldviews of the era depicts the way in which women, their rights and their liberation, are stuck in the middle of these two male defined ideals and that the issue of women’s rights effects the core of both ideologies. The traditional politician would never truly get behind women’s liberation and would always push towards patriarchal ideas; and her male dadaist peers, despite their claims of equality, revolution, and feminism would, as Höch put it, “…continued for a long while to look upon us as charming and gifted amateurs, denying us implicitly any real professional status.”

Her collage The Beautiful Girl, is another work in which Höch represents the intersections of feminism, consumerism, and mass industrialization. In this piece, the faces of women are replaced with advertisements, their bodies are interlaced with various parts of machinery and wheels and the background is made up of repeating BMW car logos and levers. The act replacing the women’s face with adverts and lightbulbs speaks to the way that modern innovation and consumerism continue to separate the woman from her place as a human individual and reduce her body and essence to a replicable product or replaceable part of a machine. This highlights the way that consumerism, despite seeming to offer the individual choices based on their ‘preferences,’ reduces everything, especially women, into mass produced, identical objects to sell. In the capitalist’s world, there is no room for individual value, rest, or innovation, there is only the infinite desire to produce, acquire, and purchase these bourgeois symbols of success.

In part two of my article, I will break down more female collage artists that have innovated and redefined collage in the second half of the 20th century to the late 2010’s; these artists would be influenced by the shifting social relationship with issues such as the Vietnam war, the civil rights movement, women’s bodily autonomy, and more recently, the resurgence of white supremacy and other far right ideologies.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

References & Further Reading:

https://www.britishmuseum.org/blog/late-bloomer-exquisite-craft-mary-delany

https://vicusyd.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/playing-with-pictures-society-cutups.pdf

https://artsandculture.google.com/story/radical-whimsy-victorian-women-and-the-art-of-photocollage/KAUhrgTXuuGwZg

https://www.artic.edu/artworks/198126/lady-filmer-in-her-drawing-room

https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/object/108ZVQ

https://trace.tennessee.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2743&context=utk_chanhonoproj

https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-radical-legacy-hannah-hoch-one-female-dadaists

https://ler.letras.up.pt/uploads/ficheiros/19287.pdf

https://sfonline.barnard.edu/the-new-woman-and-the-new-empirejosephine-baker-and-changing-views-of-femininity-in-interwar-france/2/#:~:text=The%20rise%20of%20the%20New,Frenchmen%20and%20disabling%20many%20more.

https://wheatonarthiverevue.com/essay/collaging-a-racial-other-hannah-hochs-indian-dancer-1930/